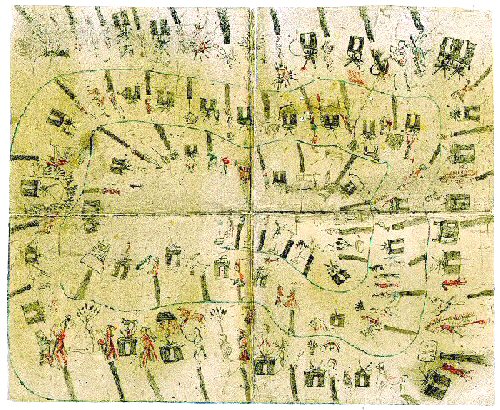

Set-t'an Annual Calendar of the Kiowa, depicting

the years 1833-1892. Painted on buffalo hide, this calendar was photographed

in 1895 by James Mooney, an ethnographer for the Bureau of American

Ethnology who lived among the Kiowa and learned of their traditions

and customs. Plate LXXV in Mooney 1898.

Kiowa Calendar

Sett'an calendar was a semiannual notation of some striking events that stirred the tribe. The winter notation or pictograph was indicated by an upright black bar below the principal figure; the summer notation was often designated by a picture showing a medicine lodge for the annual Sun Dance.

The annual calendars were correlated by Alice Marriott with the more recent calendars of George Poolaw, George Hunt, and Mary Buffalo. The Sett'an calendar ended in 1892, and the Anko monthly calendar ran from August, 1889, to July, 1892. The Anko yearly calendar ran from 1864 to 1892. Both of Anko's calendars were redrawn on the same skin. The calendars given by Miss Marriott run through 1901.

The Sett'an and Anko annual calendars give the following events:

Winter, 1832-33—Some money was captured from American traders near the South Canadian River. In the fight Guikongya ("Black Wolf") was killed. The pictograph shows a man's head with the figure of a black wolf attached to it by a line—a sort of "name-scroll" in the same way that the Maya pictures used a line issuing from the mouth to show a "speech-scroll." A sketch of a silver dollar with an eagle on it indicates the money. Twelve traders left Santa Fe with ten thousand dollars in specie packed on mules. Two men were killed in the fighting. The remaining ten men separated into parties of five. Seven of the ten finally reached the Creek Indians on the Arkansas and were saved. Until they were told by the Comanches, the Kiowas did not know the value of the silver discs; thus, they used them as decorations in their hair.

Summer, 1833—"Summer that they cut off

their heads." This picture commemorates a massacre by the Osages,

who cut off the heads of the Kiowa victims and left them in their own

copper cooking kettles. Most of the Kiowa warriors were absent, and the

village was surprised. A'date, the head chief who had allowed his village

to be attacked, was deposed and Dohasan became head chief.

Winter, 1833-34—On November 13, 1833, there occurred a meteoric

display observed all over North America. Sett'an was born the preceding

summer, and the figure of a child over the winter bar indicates his first

winter; the stars above represent the meteors. The Kiowas, then camped

on a tributary of Elm Fork of the Red River, were awakened by a bright

light, and rushed out into a night as bright as day with meteors darting

about. They awakened their children, saying, "Get up, get up, there

is something awful going on!"

Summer, 1834—The Dragoon expedition met the Comanches, Wichitas,

and Kiowas and returned a captive girl, Gunpa-ndama ("Medicine-Tied-to-Tipi-Pole"),

taken by the Osages when they had massacred the Kiowa village in 1833.

The pictograph shows a tipi attached by a line to the figure of a girl.

This meeting with the Americans opened up trade with the allied tribes,

and arrangements were made at a meeting at Fort Gibson for the subsequent

treaties of 1835 and 1837.

Winter, 1834-35—The winter that Bull-Tail was killed by the Mexicans

from Chihuahua while the Kiowas camped on the southern edge of the Staked

Plains. The pictograph shows only Bull-Tail, although several others were

killed too.

Summer, 1835—Cat-tail rush Sun Dance. After the recovery of the

Tai-me, a Sun Dance was held on the south bank of North Canadian River,

where many rushes (Equisetum arvense) grew. The pictograph shows a sketch

of the medicine lodge, and a box above it represents the Tai-me in the

rawhide box. Immediately after the Sun Dance a party of Kiowas made a

raid far down on the Texas coast and captured Boin-edal ("Big Blond"),

a German who was still living with the Kiowas in 1892.

Winter, 1835-36—To-edalte ("Big Face," or "Wolf Hair")

was shot and killed by Mexicans while on a raid in Mexico.

Summer, 1836—The Wolf Creek Sun Dance is shown by the sketch of

a wolf attached by a line to the medicine lodge. After the dance the Kiowas

moved north of the Arkansas. A portion of the Kiowas were attacked by

Cheyennes, but they threw up breastworks and defended themselves successfully.

The Kingeps went to visit the Crows.

Winter, 1836-37—K'inahiate was killed in an expedition against the

Timber Mexicans or Mexicans of Tamaulipas and the lower Rio Grande. The

wide range of the Kiowas is shown here—one band raiding in Mexico,

another band visiting the Crows on the upper Missouri.

Summer, 1837—"Summer that the Cheyennes were massacred."

The battle is shown by the conventional Indian symbol: the party attacked

defend themselves behind breastworks while the arrows fly toward them;

below is the figure of a man wearing a war bonnet. The Cheyennes came

on the Kiowas while they were preparing to hold a Sun Dance on a tributary

of Scott Creek, a branch of the North Fork of Red River, near later Fort

Elliott in the Texas Panhandle. All forty-eight of the Cheyennes were

killed, and six Kiowas lost their lives.

Winter, 1837-38—"Winter that they dragged the head." The

head of an Arapaho was dragged behind a horseman. The German captive Boin-edal,

then a little boy who had been with the Indians about two years and who

witnessed the barbarous spectacle, told Mooney in 1892 that he could still

remember the thrill of horror that passed through him.

Summer, 1838—The Cheyennes and Arapahoes organized a war party and

attacked the Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches on Wolf Creek, a short distance

above where that stream joins Beaver Creek and forms the North Canadian

River. A circular breastwork was dug and the camp was saved although the

Kiowas lost several warriors. The picture shows arrows and bullets, indicating

that the Cheyennes had some guns. Black dots with wavy lines indicated

the bullets.

Winter, 1838-39—A battle with the Arapahoes occurred, and all the

Arapahoes were killed.

Summer, 1839—The Peninsula Sun Dance was held. The peninsula was

on the south side of the Washita a short distance below Walnut Creek.

An expedition of about twenty Kiowas under Gua-dalonte against the Mexicans

of El Paso took place. At Hueco Tanks the Kiowas were attacked by Mexicans

and some Mescalero Apaches. The horses were killed, and the Kiowas were

penned

up to starve. But they climbed out of the cave, having to abandon one

wounded man, Dagoi, who accepted his fate as a warrior. Although fired

on by the Mexicans and having another man, Konate, wounded, they managed

to escape. Konate was abandoned by a spring under an arbor of branches,

and Dohasan (the elder) and others returned to their homes. On their way

they met six Coman-ches en route to Mexico and asked them to bury Konate.

The Comanches found Konate alive, helped him on a horse, and gave up their

proposed raid to bring him safely home, where he recovered. Konate assumed

a new name, Patadal, Lean Bull, which he later bestowed on another man,

known to the whites as Poor Buffalo. He said that a wolf had come to him

in his anguish, licked his wounds, and slept beside him. Then a rain came

and washed his wounds, and a spirit told him that help would come.

Winter, 1839-40—"Smallpox Winter." The Kiowas were ravaged

by the disease. The pictograph shows a man with spots all over his body.

The disease began on the upper Missouri among passengers on a steamer

in the summer of 1839. It was communicated to the Mandans and swept the

Plains, destroying perhaps more than a third of the natives. It reached

the Kiowas by way of some visiting Osages. The Kiowas and Kiowa-Apaches

fled to the Staked Plains in an effort to escape it. The terrific toll

of the Plains Indians appeared later in official reports: from 1,600 to

3,100 persons for the Mandans; from 2,000 to about 4,000 for the Arikaras

and Minnetarees; and the Blackfeet, Crows, and Assiniboins were estimated

to have lost from 6,000 to 8,000. How many persons the Kiowas lost is

not known.

Summer, 1840—Red-Bluff Sun Dance—on the north side of the

South Canadian, about the mouth of Mustang Creek in the Texas Panhandle.

The prominent event of the summer was the peace made by the Arapahoes

and Cheyennes with the Kiowas, Comanches, and Kiowa-Apaches. No mention

was made of one of their raids, however. In the summer of 1840 the Comanches

and Kiowas made a raid to the coast of Texas. They were followed and inter-

cepted at the Battle of Plum Creek, where a number of Indians were killed.

Winter, 1840-41—Hide quiver war expedition. The figure of a quiver

is shown above the black winter bar. A war expedition was made by the

old men into Mexico. They carried old bows and quivers of buffalo skin,

as all the younger warriors had already set out for Mexico carrying the

better weapons and ornate quivers of panther skin or Mexican leather.

Summer, 1841—Friends of the Kiowas, the Arapahoes, attacked a party

of Pawnees at White Bluff on the upper South Canadian and killed all of

them. The Kiowas were not present but met and joined the Arapahoes after

the battle. The Pawnees are shown in the pictograph before a white bluff—the

tribe indicated by the peculiar Pawnee scalp lock and headdress.

On "American Horse" River south of Red River (probably a branch

of the Pease River), where the whole Kiowa camp was located, some Texas

soldiers advanced and the Kiowas killed five army scouts, took their large

American horses, and fled. They returned a few days later, found the soldiers

still there, and killed another.

This was the fight with the Texan-Santa Fe expedition, August 30,1841.

The Texans heard from Mexican traders that the Kiowas had lost ten of

their warriors and a principal chief.

Mooney remarked that the Indian account, corresponding remarkably with

George Wilkins Kendall's account of the Santa Fe expedition, was handed

down orally for over fifty years without any knowledge of the printed

statement by either Mooney or his informants.

Winter, 1841-42—A'dalhaba'k'ia was killed. The pictograph shows

the man with a bird on top of his head to show the ornament of red woodpecker

feathers he always wore on the left side of his head.

Summer, 1842—Two Sun Dances were held on Sun

Dance Creek or Kiowa Medicine Lodge Creek, which enters the North Canadian

near the one-hundredth parallel. Two dreamers had been instructed to hold

dances and made their requests to the Tai-me keeper almost simultaneously.

Winter, 1842-43—There is a picture of a man with a crow in front

of his neck. This was the winter that Crow-Neck died in Wind Canyon at

"Trading River," an upper branch of Double Mountain Fork of

the Brazos. He was the adopted father of the German captive, Boin-edal.

Summer, 1843—The Nest-Building Sun Dance was held on Sun Dance Creek,

a favorite place for the dance. It was called "Nest-Building Sun

Dance" because a crow built her nest and laid her eggs upon the center

pole after the dance was over.

Kicking Bird led a raid into Texas, captured some horses, and later returned

them to a party carrying an American flag. They afterward learned the

party was Texan, and had deceived them. The Texans had two captives, a

Comanche and a Mexican. The Kiowas rescued the Comanche but left the Mexican

since no one wanted him.

Winter, 1843-44—A woman was wounded in the breast after the Nest-Building

Sun Dance. Dohasan had invited the woman to ride behind him, as was customary,

while the freshly cut trees were dragged to the lodge. Her husband was

enraged and he stabbed her. She recovered and the Chief Dohasan rebuked

her husband by saying that he ought to have better sense, that he, Dohasan,

was an old man—too old to be running after girls.

A raiding party went into Tamaulipas and killed a number of people, but

was attacked while recrossing the Rio Grande and three Kiowas were killed.

In the following winter, 1844, a clerk of Bent's Fort, called Wrinkled

Neck, built a log trading house a few miles above Adobe Walls in the Texas

Panhandle. It was also stated that the same man later built another trading

post at a spring above the first one at Giiadal Doha on the same (north)

side of the river.

Summer, 1844—Dakota Sun Dance. A number of the Dakotas visited the

Kiowas to dance and receive presents of ponies at the Sun Dance held again

at Kiowa Medicine Lodge Creek. The pictograph shows a medicine lodge with

the figure of a Dakota wearing a k'odalpa or necklace breastplate of shell

or bone tubes, known among traders as Iroquois beads. The Kiowas called

the Dakotas, who were of long-standing friendship with them, and the original

wearers of such necklaces, the "Necklace People," K'odalpa-K'inago.

Mooney says that this explanation appears to be a myth founded on a misconception

of the tribal sign for Dakota, a sweeping pass of the hand across the

throat commonly translated as "beheader."

Winter, 1844-45—A'taha'ik'i ("War-Bonnet-Man") was killed.

A raid was made by Big Bow to avenge the death of his brother in Tamaulipas.

After "giving the pipe" at the last Sun Dance, over two hundred

Kiowas, Comanches, and Kiowa-Apaches joined the party which crossed the

Rio Grande and reached the Salado. Here some Mexicans took refuge in a

fort, where the party charged them. A'taha'ik'i was killed. The fort was

fired and its defenders were killed. The party then went farther into

Mexico and had another fight in which Big Bow (grandfather of the later

Big Bow) was killed.

Summer, 1845—The Stone-Necklace Sun Dance was held at Kiowa Medicine

Lodge Creek and named after a girl called Tso-k'odalte ("Stone Necklace")

who died and was mourned during the ceremony.

Winter, 1845-46—A sketch of a house shows the trading post built

by William Bent (called "Mantahakia" or "Hook-Nose Man")

in the Texas Panhandle, just above Bosque Grande Creek. In 1844, Bent

had built a trading post higher up on the South Canadian River. Both posts

were in charge of a clerk called "K'odal-aka-i" ("Wrinkled

Neck"). The removal of Bent's operations from the Arkansas to the

Canadian seems to have marked the southward movement of the tribes.

Summer, 1846—Sun Dance when Hornless-Bull was made a Ka'itsenk'ia.

The figure shown is that of a man with a feather headdress and paint of

the Koitsenko warrior society, a part of the Yapahe or military organization.

Ten brave men formed the Koitsenko. During raids their leader carried

a sacred arrow, with which he anchored himself to the ground by means

of a black sash of elk skin and pledged himself not to retreat. If the

party was not victorious, he had to remain and die unless his comrades

pulled up the arrow. Three of the members' sashes were made of red cloth,

and six were made of elk skin dyed red. If a member became too old to

go to war, he gave his sash to a worthy younger man and received blankets

or gifts for it.

Winter, 1846-47—The winter when they shot the mustache. Mustaches,

said Mooney, were not infrequent among the Kiowas. Set-angia ("Sitting

Bear") had almost a full beard. In a fight with the Pawnees Set-angia

slipped in the snow, and a Pawnee shot him in the upper lip or mustache

with an arrow.

Summer, 1847—There was no Sun Dance, but the summer was remembered

because of the death of the Comanche chief, Red Sleeve, in an attack on

a party of Santa Fe traders at Pawnee Fork on the Santa Fe Trail. Set-angia

advised against the attack, and Red Sleeve taunted him with cowardice.

The Kiowas drew off, and Red Sleeve and his Comanches attacked the train.

Red Sleeve was shot through the leg by a bullet that entered the spine

of his horse and caused the animal to fall and pin Red Sleeve beneath

him. He called on Set-angia for help, but the Kiowa refused because of

the taunt, and the white men came up and shot Red Sleeve.

Winter, 1847-48—The pictograph shows a camp of tipis with a brush

windbreak about it. All winter the Kiowas camped on T'ain P'a, White River,

an upper branch of the South Canadian.

Summer, 1848—A Koitsenko initiation Sun Dance was held on the Arkansas

River near Bent's Fort. The figure represents an initiate with his red

body paint and sash.

Winter, 1848—49—While camped near Bent's Fort, the Kiowas

made antelope medicine for a great antelope drive. A sketch of an antelope

marks the winter. Antelope drives, which were unusual, were made when

buffalo meat was insufficient, and could be made only in winter when the

animals gathered in herds. The drive was led by the "antelope medicine

man," and the whole tribe, mounted and on foot, took part. The animals

were encircled and seized by hand or by lassos. No shooting was allowed

in the circle, but an animal that broke away was pursued and shot outside

the circle.

Summer, 1849—This was the Cramp or Cholera Sun Dance. In the spring

and summer, cholera swept the Plains; it came from the East with the emigrants

to California and Oregon. The Kiowa Sun Dance was held on Mule Creek between

Medicine Lodge Creek and the Salt Fork of the Arkansas. Cholera was brought

by visiting Osages who came to the dance. The disease appeared immediately

after the dance. The Kiowas said that half their number perished; whole

families and camps were exterminated, and many committed suicide. The

survivors scattered in different directions until the disease spent itself.

Winter, 1849—50—This winter was remembered because of fighting

with the Pawnees, securing some Pawnee scalps, and holding a scalp dance.

Summer, 1850—A sketch of a chinaberry tree over a medicine lodge

marked the Sun Dance which was held near a thicket of chinaberry trees

on Beaver Creek or upper North Canadian River near present Fort Supply,

Oklahoma.

Winter, 1850-51—The pictograph shows a sketch of a deer with antlers

and a line attached to a human head. It marked the winter that Tangiapa

(whose name signified a male deer) died. He was killed in a raid into

Tamaulipas.

Summer, 1851—Dusty Sun Dance was held on the north bank of the North

Canadian, just below the junction of Wolf Creek. Strong winds prevailed

and kept the air dusty. The summer was remembered for a fight with a band

of Pawnees, ostensibly friends, who acted treacherously and were attacked

and defeated. The Kiowas lost two prominent warriors.

Winter, 1851-52—A figure of a woman over the winter bar recalls

the "winter the woman was frozen." Chief Big Bow, then a young

man, stole a woman, a pretty one, whose husband was away on the warpath.

He took her to his home camp and left her in the woods while he went into

his father's tipi to obtain food. His father knew what he had done and

held him. Exposed to the cold, the waiting woman had her feet frozen.

"Stealing" a woman was contrary to tribal mores.

Summer, 1852—There was no sun dance. The pictograph for the summer

notation is that of a man wearing a cuirass, probably obtained from Mexico.

The Cheyenne chief, A'patate or "Iron-Shirt-Man," was killed

by the Pawnees in Kansas or Nebraska. The Kiowas and Kiowa-Apaches joined

the Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and some Dakotas in the fight against the Pawnees

but were defeated by the larger Pawnee force.

Winter, 1852-53—A picture of a horse (with hooked feet which portrayed

hoofs) held by a rope in the hand of a man portrays the loss of Set-angia's

two horses, including the finest one in the tribe, a bay race horse known

as "Red-Pet." The figure is that of the Pawnee boy who stole

the horse. The fact that this theft was the most significant event of

the winter marks the importance of the horse to the equestrian Kiowas.

Summer, 1853—Showery Sun Dance was the name given the Sun Dance

celebration because of constant rain. A black cloud, with rain descending,

and red flashes of lightning are shown over the medicine lodge.

A deliberate violation of the Tai-me rules distinguished this Sun Dance.

Ten-piak'ia, father of the historian Sett'an, broke the rules by riding

inside the camp circle with a small mirror. He afterward tried to poison

Anso'te, the Tai-me keeper, with mercury scraped from the back of the

mirror and placed in tobacco, which he gave the priest to smoke. Anso'te

took one puff and put the pipe away, refusing to smoke. Shortly thereafter,

Ten-piak'ia was thrown from his horse and killed; this was believed to

be punishment of sacrilege. It is interesting to note that there were

occasional, though rare, instances of deliberate nonconformity among some

bold spirits in the tribe.

Winter, 1853-54—After the Sun Dance of the summer, a raid was made

into Chihuahua where a mule train was attacked. As Pa'ngyagiate was striking

the mules with his bow (counting coup and sealing ownership), he was shot

and killed. The pictograph shows a Koitsenko warrior with his red sash

and shield, denoting the warrior killed.

Summer, 1854—The Sun Dance was held at Timber Mountain Creek, where

the Medicine Lodge Treaty would be signed in 1867. The pictograph portrays

a black horse joined by a line to a human figure above the Sun Dance lodge,

thus noting the death of Tsen-konkya ("Black-Horse"), a war

chief.

Stumbling Bear's brother had been killed by the Pawnees, and at the Sun

Dance, Stumbling Bear sent the pipe around to recruit a revenge expedition.

A large war party consisting of several hundred warriors from seven tribes—Kiowas,

Kiowa-Apaches, Co-manches, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, Osages, and Crows—crossed

the Arkansas and on the Smoky Hill met about eighty Sac and Fox Indians

and a few Potawatomis, recently removed from beyond the Mississippi to

Kansas. A fight disastrous to the Kiowas and their allies took place.

The Sac and Foxes, armed with rifles, killed about twenty of their enemies,

twelve of them being Kiowas. The Kiowas were impressed with the rifles

and said that "they hit every time."

Some of the Kiowas stated that the expedition was directed against the

new immigrant tribes, in an attempt to exterminate them. The report for

1854 by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs stated that the enemies of

the one hundred Sac and Foxes in the fight had numbered fifteen hundred.

The Osages had a few guns, but the other attackers had used bows and arrows.

Six of the Sac and Foxes were killed from rifle shots.6 Whirlwind, a famous

war chief of the Southern Cheyennes, had every feather shot out of his

war bonnet. He said it was the hardest fight he had ever been in, but

he believed the medicine hawk on his war bonnet had saved him.

Winter, 1854-55—Another Koitsenko warrior, Gyai'koaofite ("Likes-Enemies"),

was killed by the Osages, or Quapaws, on a horse-stealing raid.

Summer, 1855—The pictograph shows a seated man. It was a hot summer

with no Sun Dance and no grass. The horses were too weak to travel, and

the Kiowas "sat down."

Winter, 1855-56—The brother of Gyai'koaofite, A'dalton-edal ("Big-Head"),

is pictured killing an Osage to avenge his brother's death. During the

winter a large number of horses were taken in Chihuahua, and only one

man, Going-on-the-Road, was lost.

Summer, 1856—Near Bent's Fort in Colorado the Prickly-Pear Sun Dance

was held, late in the fall, when the prickly pears ripened. The fruit

was generally eaten raw, and the fleshy leaves were used in painting on

buckskin.

Winter, 1856-57—Two tipis sketched above the winter bar mark the

winter that the tipis were left behind. After the summer Sun Dance, while

camped near Bent's Fort, a war party led by Big Bow and Stumbling-Bear

proceeded against the Navahos. Lone Wolf led the rest of the Kiowas after

buffalo. Their tents were rolled up and left in care of William Bent.

On returning, they found the Cheyennes had their tipis. When they complained

to Bent, he said, "I have given them to my people." Bent's people

were the Cheyennes, as Bent had married a Cheyenne woman. A quarrel took

place, in which Lone Wolf's horse was shot and one Kiowa was wounded.

The Kiowas were driven off, and the Cheyennes kept the property

.

Summer, 1857—A Sun Dance was held on Salt Fork of the Arkansas at

Elm Creek. A Kiowa, K'aya'nte, owned a sacred medicine forked stick of

chinaberry, about four feet long, and placed it as a sacrifice inside

the medicine lodge. Next year someone found that it had reversed and sprouted.

This confirmed the mysterious power ascribed to the medicine. The stick

had been trimmed of its bark. Ten years later the chinaberry was still

growing.

Two war parties went out that summer—one against the Mexicans of

El Paso and another, with the Comanches, against the Sac and Foxes. An

engagement occurred near the location of the former battle with these

people, and several Sacs were killed.

Winter, 1857-58—The Kiowas camped near Bent's Fort in Colorado.

The Pawnees stole six bunches of horses. The Kiowas pursued them and intended

to strike, but a snowstorm stopped them when only one Pawnee had been

killed. The figure above the winter mark represents the stolen horses.

Summer, 1858—The Sun Dance was held on Mule Creek where it entered

the Salt Fork of the Arkansas. The calendar depicts a

natural circular opening in the timber, showing trees surrounding the

medicine lodge.

Winter, 1858-59—After the Sun Dance, the Kiowas made a raid into

Chihuahua and captured many horses. The Mexicans followed and attacked

the Kiowas after they had recrossed the Rio Grande. All fled save Gui-k'ati

("Wolf-Lying-Down"), who rode a mare which was delayed by a

colt. He was shot and killed. Satanta and Set-imkia made a raid against

the Utes on the upper South Canadian and killed one man.

Summer, 1859—The Cedar Bluff Sun Dance was held on the northern

side of Smoky Hill River; the Kiowas were drawn far 'J north by the abundance

of buffalo.

Winter, 1859-40—Giaka'ite ("Back-Hide") died, and a cross

was erected over his bones. The pictograph shows a man with a cross over

his head. His name—Back-Hide—is the word for a piece of rawhide

worn over the shoulders by women to protect the back when carrying wood

or other burdens.

Giaka'ite was an old man and was abandoned on the Staked Plain of Texas.

Returning to the spot afterward, a war party noted that someone had placed

a cross over his skeleton. (The year before his death, while the Kiowas

were moving, Adalpepte and his wife had met the old man on a feeble animal

far behind the main party. It was cold, and Adalpepte had given the old

man his buffalo robe to keep him warm. A year later, he was abandoned.)

Summer, 1860—There was no Sun Dance. Some of the Kiowas went south

of the Arkansas, and some went north with the Kwahadi Comanches under

the chiefs Tabananica ("Hears-the-Sunrise") and Isa-ha-bit ("Wolf-Lying-Down").

The latter group were attacked by white soldiers with allies of the Caddoes,

Wichitas, Tonkawas, and Penateka Comanches. A Comanche named Tin Knife

and a Kiowa, T'ene-badai ("Bird-Appearing"), were killed. The

Commissioner of Indian Affairs reported in 1860 that the Kiowas and Comanches

were hostile and that the army had been ordered to chastise them because

many citizens were being murdered on the Santa Fe Trail. The Penateka

Comanclies, who had settled on a Texas reservation (Clear Fork or Upper

Reservation), and the Caddoes and others from the Brazos reservation often

aided the whites. All of these Indians were moved in 1859 to Indian Territory.

Winter, 1860-61—While the Kiowas were camped on the south side of

the Arkansas, Gaabohonte ("Crow-Bonnet") raised a party to avenge

the death of his brother who had been killed by a Caddo in the preceding

summer's engagement. They went to the Caddo camp in the present Wichita

reservation and there killed and scalped a Caddo. A scalp dance was held

on the south side of Bear Creek or "Antelope-Corral River."

From this rejoicing, the place got the name of Foolish or Crazy Bluff.

A war party entered Texas about the same time but lost three men.

Summer, 1861—The pictograph shows a pinto horse tied to the medicine

lodge. It was the Sun Dance "when they left the spotted horse tied."

On the Arkansas River near the Great Bend in Kansas the dance was held.

One man performed crazy and sacrilegious acts. After he came to his senses,

he gave the horse to atone for his acts. This tying of a horse inside

the medicine lodge was never known before, but horses were sometimes sacrificed

to the sun by being tied to a tree out upon the hills. Ga'apiatan twice

sacrificed a horse in this manner—once during the cholera of 1849

and again in the smallpox epidemic of 1861-62. These were propitiatory

offerings with a prayer to save himself, his parents, and his children.

His faith was rewarded; none of his relatives died. One of the horses

offered was called "t'a-kon" ("black-eared"), considered

by the Kiowas as the finest of all horses.

A war party of seven, including one woman, went into Mexico. It never

returned. In 1894, Big Bow visited the Utes and found the woman married

to a Ute and the mother of his three children. Big Bow learned that the

others of the party had been killed. He tried to get the woman to return

to the Kiowas, but she would not leave her family.

Winter, 1861-62—The pictograph shows a spotted man. This was "Smallpox

Winter," when the Kiowas were in southwestern Kansas. A party on

its way into New Mexico to trade stopped in a small town in the mountains

at the head of the South Canadian. There they were warned of the disease.

They left, but one Kiowa had bought a blanket and insisted on bringing

it back even though he was warned not to do so. After they returned to

their home camp, this man died and the epidemic broke out. They scattered

to escape the disease.

For some years the Kiowas had been drifting eastward from their former

camping grounds on the upper Arkansas. With the large influx of whites

into Colorado following the discovery of gold at Pike's Peak in 1858,

there was a great displacement of the buffalo as well as of Indians.

Summer, 1862—There was no event of importance, but a Sun Dance was

held near the junction of Medicine Lodge Creek with the Salt Fork of the

Arkansas after the smallpox epidemic.

Winter, 1862-63—The Kiowas camped on Upper Walnut Creek, which enters

the Arkansas at the Great Bend in Kansas. Deep snow on the ground kept

the horses from getting grass, and they tried to eat the ashes thrown

out from the campfires. This was the "winter when horses ate ashes."

A war party went into the Texas Panhandle, crossing the Canadian near

Kiowa Creek and passing on by Fort Elliott. They sang the "travel

song" on Wolf Creek, and the treetops returned their echo. It may

have been due to a bluff just south of the camp, but the Indians ascribed

it to spirits. The pictograph shows a tree with a wavy line around its

top. The travel song or gua-dagya was a part of the recruiting of a war

party. The recruits and women beat on rawhide with sticks and sang the

song. It was sung at intervals after the party set out.

Summer, 1863—The picture shows a one-armed

white man over the medicine lodge. The Sun Dance was held on No-Arm's

River or Upper Walnut Creek in Kansas. It was named after the trader,

William Allison, who kept a store at the mouth of the river. Allison had

lost his right arm. In 1864, Fort Zarah was built near Allison's trading

post.

Winter, 1863-64—This was the winter that Big Head died. He was the

uncle of the later chief Go-ma-te who took the same name, Adalton-edal.

In this winter Anko began an annual calendar of events.

Summer, 1864—This was the summer of the Ragweed Sun Dance, called

thus because many weeds grew at the junction of Medicine Lodge Creek and

the Salt Fork of the Arkansas. The ragweed is pictured over the medicine

lodge. The Kiowas had an encounter with United States troops, but it was

apparently unintentional.

The Kiowas later camped near Fort Larned, Kansas. There they held a scalp

dance. Set-angia and his cousin approached the fort and were warned away

by a sentry. Not understanding, they advanced and the soldier threatened

to shoot. Thereupon Set-angia shot two arrows at the soldier, shooting

him through the body, and another Kiowa fired at him with a pistol. Panic

ensued, the soldiers' horses were stampeded by the Indians, and the Indians

abandoned their camp. They did not attack the fort, but the soldiers could

not follow without mounts. The summer was full of depredations executed

by several different tribes.

Winter, 1864-65—This was called the "Muddy-Traveling Winter"

because of mud and heavy snows. The Kiowas and some Co-manches camped

on Red Bluff on the north side of the South Canadian between Adobe Walls

and Mustang Creek. Early in the winter they were attacked by Kit Carson

with troops and Ute and Jicarilla Apache allies. The picture shows tipis

with arrows and wavy lines for bullets, symbolic of an attack. Five persons

of the Kiowas and their allies were killed, two of them women. The enemy

burned their camp, and the Kiowas had to abandon it. A Kiowa-Apache was

shot from his horse, and a Ute warrior got his war bonnet. One old Kiowa-Apache,

who was left in his tipi in the hurry of flight, was killed.

According to the Indians, most of their warriors were off on the warpath.

Their families were in the camp in charge of the old Chief Dohasan. Some

of the men went out to bring in their horses one morning and saw the enemy

creeping up to surround them. They ran back to give the alarm, and the

women and children fled while the men mounted their horses to repel the

enemy. Stumbling Bear was one of the leading warriors in the camp, and

he distinguished himself by killing one soldier and a Ute, then causing

another soldier to fall from his horse. Set-tadal ("Lean Bear")

was another warrior who fought nobly, singing the war song of his order,

the Tonkonko, which forbade him to save himself until he had killed an

enemy. The Kiowas escaped but the camp was destroyed. The enemy was repelled.

An army officer later wrote of the engagement:

"I understand Kit Carson last winter destroyed an Indian Village.

He had about four hundred men with him, but the Indians attacked him as

bravely as any men in the world, charging up to his lines, and he withdrew

Ms command. They had a regular bugler, who sounded the calls as well as

they are sounded for troops. Carson said if it had not been for his howitzers

few would have been left to tell the tale."

Carson's forces lost two soldiers killed and twenty-one wounded, several

mortally. There was one Ute killed and four wounded.

Summer, 1865 — The Peninsula Sun Dance was held — so called

from the bend of the Washita, a short distance below the mouth of Walnut

Creek.

Winter, 1865-66—Ta'n-konkya, or "Black-Warbonnet-Top,"

died on the upper South Canadian. The Anko calendar also related the death

of Chief Dohasan. The event is indicated by the figure of a wagon; Dohasan

was the only Kiowa who owned a wagon (destroyed in Kit Carson's attack).

The winter is also notable for a large trading party from Kansas led by

John Smith, called "Poomuts" or "Saddle-Blanket" from

the articles of his trading stock. Various things were traded for buffalo

hides. Smith also traded with and served as a government interpreter for

the Cheyennes, especially at the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867.

Summer, 1866—The Flat Metal (or German Silver) Sun Dance was held

on Medicine Lodge Creek near its mouth in Oklahoma. A trader brought the

Kiowas a large amount of flat sheets of German silver which they hammered

into belts and ornaments. The pictograph shows a medicine lodge and a

strip of hide covered with silver disks finished with a tuft of horsehair.

Such pendants were attached to the scalp lock. They obtained some genuine

silver disks in the old days from Mexican silversmiths near present Silver

City, New Mexico, and also used silver dollars. Charles W. Whitacre brought

the German silver to the Kiowas. He was known as "Tsoli" (Charley).

For years he had a trading store near the present agency at Anadarko,

until he died accidentally in 1882.

Winter, 1866-67—This was the winter that Ape-ma'dlte was killed.

The name signifies "Struck-His-Head-Against-a-Tree." He was

a Mexican captive and was killed on the California Road in southwestern

Texas by troops or Texans. As a member of Big Bow's raiding party, he

was trying to stampede some horses of the Texans.

Another captive, later famous, was obtained by purchase from the Mescalero

Apaches, who had stolen him near Las Vegas, New Mexico. This was Andres

Martinez who was then seven years old and taken on a raid into Mexico.

He was adopted by Set-daya-ite, ("Many Bears" or "Heap-of-Bears"),

who was killed in a raid against the Utes in 1868.

Summer, 1867—The Sun Dance was held on the Washita near the western

line of Oklahoma. The Cheyennes attended the dance. The Navahos stole

a whole herd of ponies, including a highly prized white race horse with

black ears. The three tribes, finding their horses stolen, set out against

the Navahos, then placed on the Mes-calero reservation in eastern New

Mexico, and recaptured their horses. The pictograph shows a white horse

with black ears and a black spot on his rump, over a sketch of a medicine

lodge.

At the Sun Dance there was an initiation of members of the Koitsenko.

Some who had been cowardly were degraded and had their sashes taken from

them.

Winter, 1867-68—This "Timber-Hill Winter" received its

name from the treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, called "Timber Hill

River." The pictograph is quite clear. It shows a seated white soldier

and a seated Indian shaking hands beneath a hill with trees on it. The

Anko calendar records the killing of a Navaho by a Kiowa party under White

Horse on the upper South Canadian. The Navaho man had no ears. A large

party of Kiowas and Co-manches fought the Navahos on the Pecos and defeated

them, then returned in time for the treaty.

The Kiowas received notice to come in and camp near Fort Larned from General

Winfield S. Hancock, then in command in that section. They called him

"Old-Man-of-the-Thunder" because he wore epaulets showing the

eagle or thunderbird. They were given rations, then returned to Medicine

Lodge Creek to prepare a council house, some twelve miles above their

camp (near present

Medicine Lodge, Kansas).

Philip McCusker interpreted the terms of the treaty for the three confederated

tribes. McCusker spoke only Comanche; translation into Kiowa was done

by Ba'o ("Cat"), alias Gunsadalte ("Having-Horns").

The Kiowas said that the commissioners promised them "a place to

go," schools, and food for thirty years, in the hope that they would

then learn how to care for themselves. Only a few of the Comanches were

present; most of the Kwahadi band were then on an expedition against the

Navahos.

At the peace treaty there were about 5,000 persons (850 tipis) of the

Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, and Comanche tribes, and some

600 whites, including commissioners, aides, a part of the Seventh infantry,

and various interested groups—probably the largest Indian encampment

ever held on the Plains.

Summer, 1868—The Sun Dance was held near where the treaty was made.

The Cheyennes and Arapahoes frequently held their Sun Dance there separately

from the Kiowas but also attended the Kiowa dance, as did many of the

Comanches, who only once had a dance of their own.

The summer was noted for a disastrous battle with the Utes, when the Utes

captured forever the Kiowas' sacred palladium. Some two hundred warriors

smoked the pipe and, led by Patadal ("Poor-Buffalo" or "Lean

Bull"), moved against the Navahos to revenge the Ute's killing of

Lean Bull's stepson. Many Bears took with him two small Tai-me images.

As the party moved out, the omens were unpropitious. Taboo to the Tai-me

were bears, skunks, rabbits, and looking glasses. First a skunk crossed

their path; then it was discovered that the Comanches were wearing their

looking glasses or mirrors. They refused to give them up, but they did

conceal them at a camping place. One night the Kiowas smelled bear cooking.

The sacrilegious Comanches were broiling bear over a fire. This was bad.

Some of the warriors turned back. Many Bears trusted to his powerful medicine

and went on.

They met the Utes under the leadership of Kaneatche, head chief of the

Utes and Jicarilla Apaches (after his death Ouray succeeded him). The

Utes killed seven, including Many Bears and his adopted son. (Many Bears

had ridden a balky horse and had dismounted. When his son returned to

save him, both were slain.) His friend Pa-gunhente was also killed. The

sacred images were taken by the Utes, who later suffered such bad luck

that they gave the images to the trader Lucien Maxwell, who kept them

in his store. The Utes said that the Kiowas were afraid to go there and

that they were later lost. A brother of George Bent, of the noted Bent

family, saw the "medicine." They were two small carved stones,

one having the shape of a man's head and bust, decorated and painted,

and one having the shape of a bear's kidney.

The Kiowas mourned their loss. They moved down to the Wash-ita and camped

near Black Kettle of the Cheyennes, whose village would soon be destroyed

by Custer. Steps were then being taken to confine the Indians on the reservation.

Winter, 1868-69—A small raiding party descended upon the Texans,

and Tanguadal was killed by a white man. The pictograph shows a man carrying

a medicine lance or zebat. The dead warrior had been the hereditary owner

of a medicine lance or arrow lance. Satanta then claimed the hereditary

right to the lance through marriage into the family of one of Tanguadal's

relatives. Satanta did not get the lance so he made one for himself, similar

to Tanguadal's but with two arrow points—an ornamented wooden point

(ceremonial) and a steel point (for actual use).

Stumbling Bear led a group to the Canadian to bury the bones of those

killed with Many Bears by the Utes.

Summer, 1869—This was the summer of the War Bonnet Sun Dance. Although

the Kiowas resided on the reservation, they moved away from it to hunt

and dance. This Sun Dance was held on Sweetwater Creek near the western

line of Oklahoma. Big Bow returned with a party that had gone on a revenge

raid against the Utes; he brought back the war bonnet of a Ute whom he

had killed.

Winter, 1869-70—A bugle is pictured over the winter sign. The Kiowas

were camped on Beaver Creek near Fort Supply, Oklahoma. It was a winter

of chronic alarm. The Cheyennes were on the warpath and were hard pressed

by Custer. During this time a party of young men or probably Satanta blew

a bugle on returning to camp, and the Kiowas, fearing soldiers, fled.

Summer, 1870—The Sun Dance was held on the

North Fork of Red River in present Greer County, Oklahoma. Seeds of corn

and watermelon brought by the traders had been thrown down, and had sprouted

in the fall. This gave the name "Plant-Growing Sun Dance" to

the dance.

Winter, 1870-71—The bones of young Set-angia were brought home,

and the picture shows a sitting bear over a man's skeleton. In the spring

of 1870, Set-angia, second son of Chief Set-angia, was shot and killed

in Texas. The father, almost crazed, went to Texas, found the bones, put

them in fine blankets, bundled them on the back of a red horse, and brought

them home. On the return journey he killed and scalped a white man.

Set-angia placed the bones in a special tipi and gave a great feast in

the name of his son. Until his death, Set-angia venerated the bones and

carried them about on horseback. After Set-angia was killed at Fort Sill,

his son's bones were buried. The young Set-angia was a favored child,

ade, and held the office of tonhyopde, the pipe bearer or leader who went

in front of the young warriors on a war expedition.

Another event of the winter, recorded by the Anko calendar, was the killing

of four Negroes in Texas by a party led by Mama'nte ("Walking-Above").

Britt Johnson, the Negro who had traded for the return of the Fitzpatrick

and Durgan captives (and of Johnson's own family as well) in 1864, was

one of those killed.

Anso'te ("Long-Foot") also died in this winter. He had been

the Taime keeper for forty years. There was no Sun Dance for two years

until his successor was elected.

Summer, 1871—The Anko calendar notes the death of Konpa'te ("Blackens-Himself"),

who was shot in a skirmish with soldiers. The Sett'an calendar records

the arrest of the chiefs Satanta, Set-angia, and A'do-ette ("Big

Tree"), who had not ceased their raids into Texas. On May 17,1871,

a party of one hundred warriors attacked Warren's wagon train in Texas

and killed seven men and captured forty-one mules. Lawrie Tatum, agent,

called on the commander at Fort Sill to arrest Satanta, Big Tree, Big

Bow, Eagle Heart, and Fast Bear. Only three were arrested and imprisoned.

By order of General Sherman, they were sent to Texas to stand trial. On

the way Set-angia attacked the guard and was himself killed. Satanta and

Big Tree were later confined in the penitentiary at Huntsville, Texas.

Winter, 1871-72—Some of the Kiowas camped on a branch of Elk Creek

of upper Red River. Others camped near Rainy Mountain on the Washita.

A large Pawnee party visited for peacemaking and were given horses by

the Kiowas. The pictograph shows three Pawnee heads above the winter bar.

(The Pawnees also visited the Washita in 1873 and determined to move to

Indian Territory, which they did in 1875.) There was a mistake in the

date by the calendar maker. Notices by Battey and others gave the date

as 1872-73. Battey was with Kicking Bird, camped on Cache Creek, when

forty-five Pawnees came to visit in March, 1873; he described the gift-giving,

the peace, and the dance that followed.

Summer, 1872—There was no Sun Dance. The Anko calendar records a

drunken fight between Sun Boy and T'ene-zepte (Bird-Bow), in which Sun

Boy shot his opponent with an arrow". A large raid into Kansas took

place, and the Kiowas captured a large number of mules. A Mexican captive,

Biako (Viejo), was shot but later recovered. The Kiowa chiefs were trying

to stop the raids at this time in order to conform to the demands of the

government, but the tribe was split into factions.

Winter, 1872-73—The Sett'an calendar records a visit of the Pueblo

Indians, who came to trade biscocho, or bread, and eagle feathers for

horses and buffalo robes. The pictograph shows a Pueblo Indian, with his

hair tied into a bunch behind, driving a burro with a pack on its back.

(The Pawnees visited in the fall, and the Pueblos came in the winter.)

The Anko calendar records the burning of the heraldic tipi, hereditary

in the family of Dohasan, known as the "Tipi with Battle Pictures,"

which had occupied second place in the ceremonial camp circle.

Summer, 1873—The Sun Dance, held on Sweetwater Creek, was described

in detail by Thomas Battey who visited it. The Indians were much concerned

over the promised release of Satanta and Big Tree. Battey had to tell

them that the Modoc war (in California) had affected the release and cautioned

them to wait peaceably. Some of the Kiowas, along with some of the Coman-ches,

were hostile to the government. While the dance was under way, Pa-konkya

("Black Buffalo") "stole" the wife of Guibadai ("Appearing

Wolf"), who in retaliation killed seven of Pa-konk-ya's horses and

took a number of others according to tribal mores. A threat to kill the

seducer brought the Tonkonko dog soldiers to interfere. Both the Sett'an

and Anko calendars recorded the event. Pictured by the side of the medicine

lodge, the horse bleeds from an arrow.

Winter, 1873-74—This was the winter of Satanta's return (October

8, 1873). The pictograph shows the red tipi and the figure of Satanta,

distinguished by a red headdress. The Anko calendar records the killing

in Mexico of two sons (i.e., one son and one nephew) of Lone Wolf. Lone

Wolf went to bury his son, and from then on, was hostile to the whites.

Summer, 1874—The Sun Dance was "at the end of the bluff,"

near Elm Creek in Greer County, Oklahoma. Satanta gave his medicine or

arrow lance to Ato-t'ain ("White Cowbird"). There were only

two lances of this kind; one belonged to Satanta, the other belonged in

the family of the deceased Tanguadal.

Winter, 1874-75—This was the winter "that Big-Meat was killed."

The southern Plains tribes, including a large party of the Kiowas, went

together on the warpath, in what became known as the Outbreak of 1874.

After the fight at the Wichita Agency at Anadarko in August, 1871, the

Comanches fled to the Staked Plain and the Kiowas, to the head of the

Red River, whence they were pursued by troops. A horse-stealing raid into

New Mexico occurred also. On its return, it was suddenly attacked by soldiers.

Gi-edal and one other were killed. At the close of the campaign, when

the fugitives were returned to Fort Sill, a number of the hostiles were

sent to Fort Marion, Florida.

Summer, 1875—The Sun Dance was held near Mount Walsh in Greer County,

Oklahoma. It was called the "Love-Making Sun Dance" because

some young men "stole" two girls. Troops accompanied the Kiowas

because conditions were still unsettled since the outbreak.

Winter, 1875-76—In this winter 3,500 goats and sheep were issued

to the Kiowas. The calendar shows a goat over the winter bar. These animals

(and cattle) were bought by selling the Kiowa ponies—the idea was

to make the hunting Kiowas into pastoral herders. About 600 cattle were

distributed. The allied tribes had 16,000 horses and mules, reported officially,

in 1874. After the outbreak, they had only 6,000 left; they were literally

"unhorsed" and reduced to foot. The sheep and goat experiment

was a failure, but some success was made with the cattle.

Summer, 1876—The Sun Dance was held on Sweetwater Creek. While it

was going on, Mexicans stole all of Sun Boy's horses. The Kiowas pursued

the culprits, but their mounts gave out and they failed to get the stolen

horses back. The calendars record the summer with a picture of the medicine

lodge and horse tracks. The Tai-mepriest Dohente ("No-Moccasins")

died and was succeeded by Set-daya-ite ("Many Bears"), who had

charge of this dance. (He was the uncle of Many Bears, killed by the Utes.)

Later his cousin (called brother) Taimete had charge of the Tai-me.

Winter, 1876-77—This season was remembered by the killing of the

woman A'gabai ("On-Top-of-the-Hill"), by her husband lapa ("Baby").

It had occurred sometime after the summer Sun Dance. The woman was ill.

She promised lapa, a medicine doctor, that she would marry him if he cured

her. He did cure her and she married him, but she soon left him and for

this he stabbed her. Agent Haworth asked the chiefs to arrest the man.

(They said they would kill him if the agent wanted them to do so.) Dangerous

Eagle and Big Tree made the arrest. The man was confined with a ball and

chain for several months, and worked around the guardhouse. The chiefs

requested that his life be spared, as "he was young and foolish and

did not know the white man's laws or road."

Anko's calendar records the enlisting of twenty Kiowa scouts at Fort Sill;

Anko was one of them. The first scouts were organized in 1875.

Summer, 1877—The troops accompanied the Kiowas to their Sun Dance

encampment on Salt Fork of the Red River. It was called the "Star-Girl-Tree

River Sun Dance," named for a sapling used in a sacrifice to the

star girls or Pleiades. The summer was 'noted for an outbreak of measles

which killed more Kiowa children than would the measles epidemic of 1892.

The government school was turned into a hospital when its seventy-four

children became sick, but not one child died there.

Winter, 1877-78—A party of the tribe camped near Mount Scott, and

the remainder camped at Signal Mountain, which was named for a stone lookout

station built in 1874. The pictograph shows a house on a mountain. The

Anko calendar noted that buffalo were hunted at Elk Creek, called "Pecan

River."

The winter was noted for an epidemic of fever. In the fall of 1877 the

government built six-hundred-dollar houses for ten prominent chiefs of

the three tribes, including Stumbling Bear, Ga'apia-tan, Gunsadalte ("Cat"),

and Sun Boy of the Kiowas, and White man and Taha of the Kiowa-Apaches.

Summer, 1878—The picture shows two medicine lodges, for the Sun

Dance was repeated. The dances were held on the North Fork of Red River.

Part of the Kiowas had gone to the Plains in the western part of the reservation

to hunt buffalo, while the rest had stayed at home. Since each group had

pledged a Sun Dance, two were held. Troops again escorted the buffalo

hunters to the dance.

Winter, 1878-79—Both calendars record the killing of Ato-t'ain ("White

Cowbird"), to whom Satanta had given his medicine lance. Satanta

committed suicide in Huntsville penitentiary at about the same time.

Ato-t'ain was the brother of Chief Sun Boy, also known as Arrowman. Ato-t'ain

was killed by Texans while with a party that had gone to hunt buffalo,

which were becoming scarce, in what is present Greer County, Oklahoma.

The Indians had permission of the agent for this unusual winter hunt,

and were accompanied by troops. When nothing was done about the murder,

some Indians slipped into Texas and killed a white man named Earle for

revenge.

Summer, 1879—This was the year of the Horse-Eating Sun Dance. A

horse's head appears above the medicine lodge in the Sett'an calendar.

The dance was held on Elm Fork of Red River. The buffalo were so few that

the Indians were obliged to kill and eat their ponies during the summer

to keep from starving. This was the date of disappearance of the buffalo

from the Kiowa country. The official report stated that "the Indian

must go to work and help himself or remain hungry on rations furnished,"

since buffalo meat could no longer support them.

Winter, 1879-80—This was the Eye-Triumph Winter. Kaasa'-nte ("Little

Robe") and several other persons went to the North Fork of Red River

to look for antelope and probably for their old enemies the Navahos, who

had removed to a reservation in New Mexico but still penetrated the Plains.

One of the party, Pododal, believed that an owl (believed by the Kiowas

to be an embodied spirit) had warned him that the Navahos would steal

their ponies.

That night Pododal fired at something. In the morning they followed a

bloody trail but turned back. Again came word from the owl that they would

find a dead Navaho. In the morning they found an eye of a dead Navaho.

With this, they returned to have an "eye" (attached to a pole

like a scalp) dance.

Summer, 1880—There was no Sun Dance; a buffalo could not be found.

The Anko calendar recorded the death of a large, tall chief named Pabote

(American Horse). He was buried in a coffin by the whites. Anko would

not mention the name of American Horse, according to Kiowa custom. Three

years later he consented to do so. Other names used in the calendars were

similarly not mentioned for years.

Winter, 1880-81—A house was shown over the winter mark. It was probably

the house of Paul Zontam, who returned from the East as an ordained Episcopal

minister. There was also a visit from the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico.

Summer, 1881—The Hot Sun Dance was held in August on North Fork

of Red River. A solitary buffalo was found. The Sett'an calendar also

recorded that a young man, Masate ("Six"), had a hemorrhage.

"Six" referred to the man's twelve fingers and twelve toes;

his brother, Bohe, also had six fingers on each hand. These malformations

were rare among the Indians.

Winter, 1881-82—This was the "winter when they played the do-a

medicine game." Pa-tepte, or Datekan, and his rival, the Kiowa-Apache

chief and medicine man Daveko, sought honors for the most powerful medicine.

The Kiowa won. It was said that Pa-tepte tried to revive the old customs

and amusements. The do-a or tipi game was played inside the tipi. It was

the "hunt the button" game—a guessing game. The button

was a small, fur-covered stick. One group played against another. The

game was played by both sexes but never together. It was accompanied by

one of the peculiar do-a songs, in which members of the group joined.

Points were scored by tally sticks, and wagers were made. The games often

lasted far into the night.

Summer, 1882—There was no Sun Dance. Dohasan (nephew of the former

chief), whose hereditary duty it was to procure a buffalo, could not get

one. The Anko calendar noted the death of a beautiful girl, Patso-gate

("Looking-Alike"), a daughter of Stumbling Bear.

The Sett'an calendar noted the attempts of Datekan or Pa-tepte | ("Buffalo-Coming-Out")

to bring back the buffalo. The Indians were much excited. They could not

accept the fact that the buffalo were gone, but believed that they had

gone underground. Originally, according to Indian mythology, the buffalo

lived underground and were released by the hero god Sindi. Datekan sought

to release them again. Many people believed him, brought him gifts, and

obeyed him implicitly. Big Tree and other skeptics refused to take part.

Finally, he said his medicine had been ruined by violations of taboos

and that they must wait five years longer for the buffalo's return.

Winter, 1882-83—The Sett'an calendar recorded the death of a woman,

Bot-edalte ("Big Stomach"). The Anko calendar recorded that

the Indian police camped this winter on Elk Creek of North Fork of Red

River. There the Texas cattle trail crossed, and the police were on hand

to keep cattle off the reservation. Quanah Parker, chief of the Comanches,

persuaded the allied tribes to lease their grasslands to the cattlemen.

Summer, 1883—The Nez Perce Sun Dance was held, so called because

the Nez Perces came to visit the Kiowas. The Nez Perces, intercepted in

Montana by General Nelson Miles, were sent to Fort Leavenworth, then assigned

to a reservation in Indian Territory. In 1885, after much unhappiness

and illness, they were returned to reservations in Washington and Idaho.

The Nez Perces danced with the Kiowas at "Apache Creek" (Upper

Cache Creek). Set-daya-ite ("Many Bears"), keeper of the Taime

medicine, died, and the office was taken by Taimete ("Taime-man").

Winter, 1883-84—The Sett'an calendar had a picture of a canvas house

with smoke issuing from it. It was said to be the house of Gakinate ("Ten"),

the brother of Lone Wolf. A large number of children went this winter

to the Chilocco Indian School, near Arkansas City, Kansas. A party of

Dakotas also paid the Kiowas a visit to dance with them.

Summer, 1884—No Sun Dance was held. The agent said that he hoped

"we have heard the last of the dance." The Anko calendar noted

the hauling of government freight by the Kiowas, under a policy of hiring

the Kiowas to get them to adopt the white man's industries. Most of the

freight came from the railroad at Caldwell, Kansas, a distance of ISO

miles. The Indians received nearly $8,000 during the year for this work,

which they performed well.

Winter, 1884-85—The Sett'an calendar shows a house over the winter

mark, indicating that the Kiowas were beginning to build houses for themselves.

In 1886 it was officially stated that only nine families lived in houses,

while all the rest lived in tipis. The Anko calendar recorded the "stealing"

of another man's wife by Ton-ak'a ("Water-Turtle"), a medicine

man. The injured husband whipped his wife and killed a number of Ton-ak'a's

horses.

Summer, 1885—The Little Peninsula Sun Dance was held in a bend of

the Washita about twenty miles above the agency. Doha-san went to the

Staked Plain to get a buffalo. The Anko calendar noted that the Comanches

received their first grass-lease money. The Kiowas did not make leases

until a year later.

Winter, 1885-86—The outstanding event mentioned in both calendars

was a prairie fire that destroyed much of the property of Te'bodal's and

A dal-pepte's camps, northwest of Mount Scott. It occurred while most

of the tribe had gone to the agency for rations.

Summer, 1886—There was no dance; no buffalo could be found. The

Anko calendar records that Anko enlisted in the agency police force and

that the Kiowas received their first money for grass leases.

Winter, 1886-87—The suicide of Peyi ("Son-of-the-Sand"),

nephew of Sun Boy, was noted in both calendars. He took a horse without

permission and was reproved for it. He was hurt and said, "I have

no father, mother, or brother, and no one cares for me." He killed

himself with a revolver. The Indians were very sensitive to reproof or

derision, a most effective means of social control in primitive societies,

and often took their own lives when they suffered sharp ridicule.

Summer, 1887—The Oak Creek Sun Dance was held, and the agent said

that it was held with his permission but with the understanding that it

was to be the last and it was not to be "of a barbarous nature."

It was held on a tributary of the Washita above Rainy Mountain Creek.

The buffalo for the dance was bought from Charles Goodnight, who kept

a small herd of domesticated buffalo on his ranch in the Palo Duro Canyon

area. Another payment of grass money was received by the Kiowas.

Winter, 1887-88—This winter, in addition to a money payment, the

Indians received a large number of cattle in part payment of their grass

money. The calendars show a cow's head over the winter mark.

Summer, 1888—No Sun Dance was held. The agent was instructed to

prevent the dance, and even to call on the military, if necessary. The

Anko calendar noted the preaching of the prophet Pa-ingya, who claimed

to be invulnerable to bullets. He advocated the destruction of the whites

and caused great excitement. The agent said that the Kiowas were troublesome

and followed the bad advice of Pa-ingya and Lone Wolf, refused to plant

their seed, and took their children out of school. The prophet predicted

that wind and fire would clear the white man off the land; then he would

restore the buffalo and the old way of life. Sacred new fires were made,

and the people were gathered in the western part of the reservation near

Lone Wolf's camp. Sun Boy and Stumbling Bear were skeptical and refused

to follow Pa-ingya. The prophecies failed and the Kiowas lost hope. Nothing

was done to punish the prophet.

r Winter, 1888-89— The Sett'an calendar recorded that during the

winter the Kiowas camped on the Washita. The Anko calendar noted the death

of Chief Pai-talyi ("Sun Boy") .

Summer, 1889 — There was no Sun Dance, and everyone remained at

home on his farm. Grass money was received, and a son of Stumbling Bear

died.

Winter, 1889-90 — The Kiowas spent the winter in their camp on the

Washita. Another grass payment was received. The Comanches visited the

Kiowas to perform the iam dance. The dance had as a main feature the formal

adoption of a child of the other tribe by the visitors. Two men danced

while the rest sat around. There was an exchange of horses by the visited

tribe for presents placed on the ground by the visitors. At the end of

the ceremony the adopted boy was returned to his tribe. The same dance

was known among the Wichitas and Pawnees.

Summer, 1890 — A Sun Dance was started but was stopped by the military

forces. The tribal circle had been formed and the center pole placed when

the dance was stopped. A buffalo could not be had, so an old buffalo robe

was put over the pole. Quanah Parker sent word to Stumbling Bear to advise

the Kiowas to stop the dance or the soldiers would kill them and their

horses. Stumbling Bear sent two young men to the encampment to tell them.

After much discussion, they dispersed.

Winter, 1890-91—This was the winter that Sitting Bull, the Arapaho

prophet of the Ghost Dance, came. The human figure above the winter mark

signified Sitting Bull. Almost the whole tribe attended the first dance

on the Washita at the mouth of Rainy Mountain Creek. Apiatan ("Wooden

Lance") went to visit the prophet Wovoka, to investigate the truth

of the reports about the Ghost Dance religion. He returned in February,

1891. The Kiowas were convinced of the falsity of the doctrine of the

return of the buffalo and the revival of the dead.

The Anko calendar recorded the death of three schoolboys who fled the

government school. One had been whipped. They were frozen during a terrible

blizzard. An outbreak was feared, but Captain H. L. Scott was sent to

investigate and the Indians were quieted.

Summer, 1891—There was no Sun Dance. The event of the summer was

the killing of P'odala-nte, or P'ola'nte ("Coming Snake") in

Greer County, Oklahoma. He was shot by a white man in self-defense.

The Kiowas visited the Cheyennes during the summer.

Winter, 1891-92—The Sett'an calendar records the enlistment of the

Indians, chiefly Kiowas, at Fort Sill. They became Troop L of the Seventh

Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant (later Captain) H. L. Scott.

Summer, 1892—The summer was noted for a measles epidemic. Both calendars

show a human figure covered with red spots. The children were sent home

from the government school where the disease started. This spread the

infection, and the Indians made the mistake of trying to wash off the

spots in cold water.

Mooney said that when he returned to the Kiowa reservation in the early

summer of 1892, deaths were still occurring, and nearly every woman in

the tribe had her hair cut off in mourning and her face and arms gashed

by knives. Some had even chopped off a finger in grief. The men also had

their hair cut in mourning and cuts on their bodies. Wagons, houses, tipis,

and property were burned, and horses and dogs were shot over the graves

to accompany their owners to the next world. During 1892, 221 Kiowas and

Kiowa-Apaches died because of this epidemic. Dr. J. D. Glennan, attending

surgeon to the Indian Troop at Fort Sill, distinguished himself in treating

the stricken Indians. The Kiowa soldiers got together a sum of money to

give him a horse, the favored gift of the Kiowas, but since he already

had a horse, a gift of silver was given him.

Grass money was received during this summer. Noting the value of the money,

the Indians sent a group to Washington to negotiate leases for the whole

reservation. Quanah, Lone Wolf, and White Man were chosen to represent

the Comanches, Kiowas, and Kiowa-Apaches, respectively. Permission was

granted and leases were made, producing for the three tribes about $100,000

a year.

Under the new and old leases, $70,000 (already due them) was paid, marking

an era in their history. Some of the money was invested in building homes.

About sixty homes were built within the year. The agent was encouraged

to say that "in the future" the tipis would be banished and

replaced by "comfortable houses."

The yearly calendars ended here. Later calendars of George Poolaw, George

Hunt, and Mary Buffalo continued some of the important events.

Some of the incidents of later years are unexplained by the drawings.

In 1892-93, Big Bow visited the Pueblos. In 1893, Be-hodtle won the Fourth

of July beauty contest in Anadarko. The winter of 1894-95 was when "they

took the horses away from us." A big camp meeting was held in 1895,

and 1895-96 was noted for the issuance of cattle. In 1897, Black Beaver

and Crow died. During the winter of 1897-98, "they made the trip

to Washington." In 1899 came the smallpox summer, and in the summer

of 1900

Sources

Mooney, "Calendar History," 254-379, and Plate

LXXV, following p. 254 ,( 298 , citing the Report of the Commissioner

of Indian Affairs, 1854. Old traders estimated the number assembled on

the Arkansas at twelve to fifteen hundred lodges, even including the Texas

or "Woods Comanches," and the number of horses and mules at

from forty to fifty thousand. This assemblage, intended to wipe out the

immigrants, was doomed to failure)

For a comparative table of the calendars of Sett'an, George Poolaw, George Hunt, and; Mary Buffalo, see Alice Marriott, The Ten Grandmothers, 142-154, 292-305. Marriott adds (in the Poolaw calendar) that the Taime god was stolen, along with several Kiowa women, by the Osages. One of the women returned with the Taime in March. (Marriott, The Ten Grandmothers, 292.)

This information compiled, prepared and submitted to this site by Ethel Taylor and remains the property of the submitter

NOTICE: Ethel Taylor grants that this information and data may be used by non-commercial entities, as long as this message remains on all copied material, for personal and genealogical research. These electronic pages cannot be reproduced in any format for profit, can not be copied over to other sites, linked to, or other presentation without written permission of Ethel Taylor.

7-16-2007

Background Courtesy Silverhawk.